Neurofeedback / EEGBiofeedback Therapy

What Experts are Saying?

Frank H. Duffy (2000), a professor and pediatric neurologist at Harvard Medical school, recently stated that scholarly literature now suggests that neurofeedback “should play a major therapeutic role in many difficult areas. In my opinion, if any medication had demonstrated such a wide spectrum of efficacy it would be universally accepted and widely used”.

D. Corydon Hammond, a distinguished Professor Emeritus at University of Utah, school of medicine suggests that neurofeedback is an encouraging development that holds promise as a method for modifying biological brain patterns associated with a variety of mental health disorders–particularly because unlike drugs, electroconvulsive therapy, and intense transcranial magnetic stimulation, it is non-invasive and seldom associated with even mild side effects.

How Neurofeedback helps patients tamp down their fears

Source: Bruce Fellman, March 19, 2014. Retrieved from: https://world.yale.edu/faculty/michelle_hampson

Tiny parts of the brain, School of Medicine researchers are discovering, can have a huge impact on our lives. Michelle Hampson, Ph.D., and Judson A. Brewer, M.D., Ph.D., are leading teams that use real-time fMRI and what’s known as neurofeedback to try to teach people how to control brain activity and combat such problems as anxiety, addiction, Tourette syndrome, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), as well as more mundane self-imposed roadblocks to success.

Hampson, an assistant professor of diagnostic radiology, in collaboration with Christopher Pittenger, Ph.D., M.D., associate professor of psychiatry, has been working to develop treatments for people afflicted with obsessive-compulsive disorder. One common symptom of this disorder is contamination anxiety (CA).

Sufferers can be crippled by fears of infection by anything from microbes to moral turpitude. Previous research suggests that the problem arises from hyperactivity in the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). Existing therapies are not always reliable, and known drugs are not always effective, so Hampson tried using real-time images of the overwrought brain and neurofeedback methods to enable subjects to calm things down. The team worked with 20 healthy adults, all of whom had CA.

While in an fMRI scanner, subjects were shown a series of such anxiety-provoking photos as moldy fruit and skin infections, along with such neutral pictures as a backpack and a tranquil countryside. The subject’s task was to try to control hyperactivity in the OFC. Half the group saw a genuine real-time line graph that provided neurofeedback by depicting OFC activity; the control group watched a sham graph.

Both groups attempted to manipulate the graph—and control their OFC activity—by using anxiety-lowering strategies. There was no one-size-fits-all approach—some participants tried to tamp down their feelings in response to a picture, while others invoked religious beliefs, said Hampson, whose study was published online on April 30 in Translational Psychiatry. “Not only were the subjects in the treatment group significantly better at controlling their CA, but the changes persisted for at least several days.”

Hampson is also working with real-time fMRI and neurofeedback as a way to enable patients to control the tics associated with Tourette syndrome, and she and other researchers are investigating their use as a treatment for PTSD. “We look for mental disorders with a distinctive brain signature—either hyper- or hypoactivity—that can be spatially localized,” Hampson explains. “If we know what’s unhealthy in terms of brain activity, we can try to come up with specific neurofeedback strategies that move the pattern in a healthy direction.”

Of course, one group of people—experienced meditators—has been using neurofeedback techniques for thousands of years. Brewer, assistant professor of psychiatry and a veteran meditator, has studied practitioners of this ancient discipline. Using real-time fMRI and neurofeedback, Brewer and his colleagues have figured out how meditation can control an oddly fundamental brain behavior called mind-wandering. “This must have been adaptive at one point in our evolution, but we no longer know how to turn it off,” he explains. Run-of-the-mill daydreaming can be counterproductive enough, but the former soldiers he works with at the Veterans Administration Healthcare System in West Haven may be utterly disabled by their inability to stop recurrent war visions. To help vets and others, Brewer and his team are especially interested in the posterior cingulate cortex (PCC), one of the major hubs of a mind-wandering circuit called the default mode network.

“The PCC is activated when you’re anxious, when you’re thinking about yourself, when you’re planning for the future, and when you’re experiencing cravings—any time you get caught up in something,” said Brewer. “It’s the big mover and shaker.” But when it moves and shakes too much, one untoward result, he continues, is that “we tend to get in our own way.” In an investigation using real-time fMRI and neurofeedback soon to be published in NeuroImage, Brewer and his team compared the ability of meditators and non-meditators alike to dampen the PCC. Not surprisingly, the meditators were more than up to the challenge. “Meditators, through years of practice, have learned how to get caught up in the moment and, maybe more important, how to let go,” said Brewer, who directs the Yale Therapeutic Neuroscience Clinic at the VA. “A wandering mind is an unhappy mind,” Brewer explains. “We can help people get out of their own way.”

What is Neurofeedback therapy?

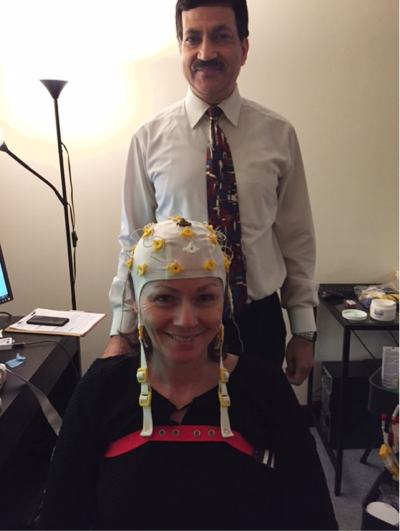

Neurofeedback is also called EEG Biofeedback, because it is based on electrical brain activity, the electroencephalogram, or EEG. Neurofeedback or Neurotherapy is a safe, non-invasive therapeutic intervention that is used to treat a variety of conditions including autism, ADHD, anxiety, LD, cognitive impairments, chronic pain, headaches, migraines, fibromyalgia, chronic fatigue syndrome, PTSD, substance abuse disorders, stress and sleep issues.

Neurofeedback is training in self-regulation. Self-regulation is a necessary part of optimal brain performance and function. Self-regulation training allows the nervous system to function better.Biofeedback affecting both mental aspects as well as physical aspects can have a very positive impact, even though indirect improvements (Nelson 2007). Recently it has been found that the behavior in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) improved in children whose parents favored a non-pharmacological treatment.

How does it work?

It helps to re-train the brain and or optimize the functioning of the entire brain by removing barriers and improving the connections and brainwave activity in a certain region of the brain or among different regions of the brain. It releases the old stuck or abnormal patterns to create new and more effective, stronger and organized patterns. Training protocols are generated from the initial QEEG brain mapping. Training involves audiovisual feedback that involuntarily teaches the individual to self-regulate the abnormal brain wave patterns that are presented to them on a computer screen in a number of ways.

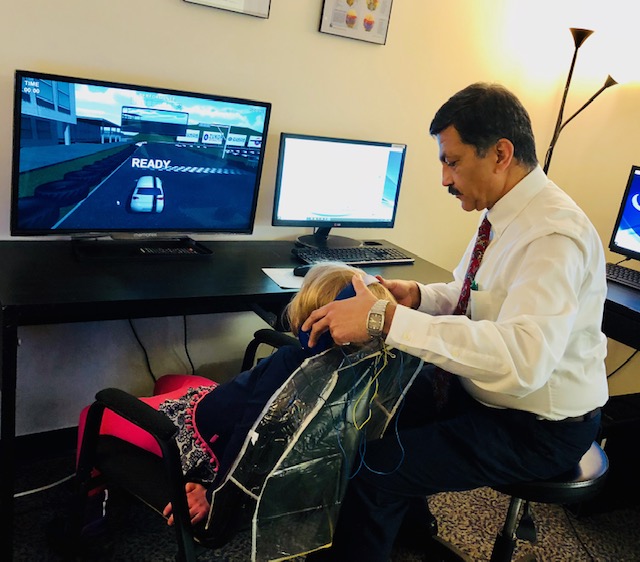

During a neurofeedback session, sensors detect your brainwaves to see your brain in action. A computer compares your brain activity to targets or goals for you to reach. Feedback from music being played and changing images can tell you immediately when your brain reaches your goal (threshold) and when not – when you are activating or suppressing the target area of the brain.

There are three types of Neurofeedback:

– Traditional Neurofeedback

– Coherence (Communication) Training

– Z-Score Training